Kubernetes was never built for efficiency.

Years ago, when we were still focused on cloud development environments, our Kubernetes bill increased rapidly. We assumed it was normal and due to heavier usage from developers. But when we pulled the actual cluster data, the picture changed.

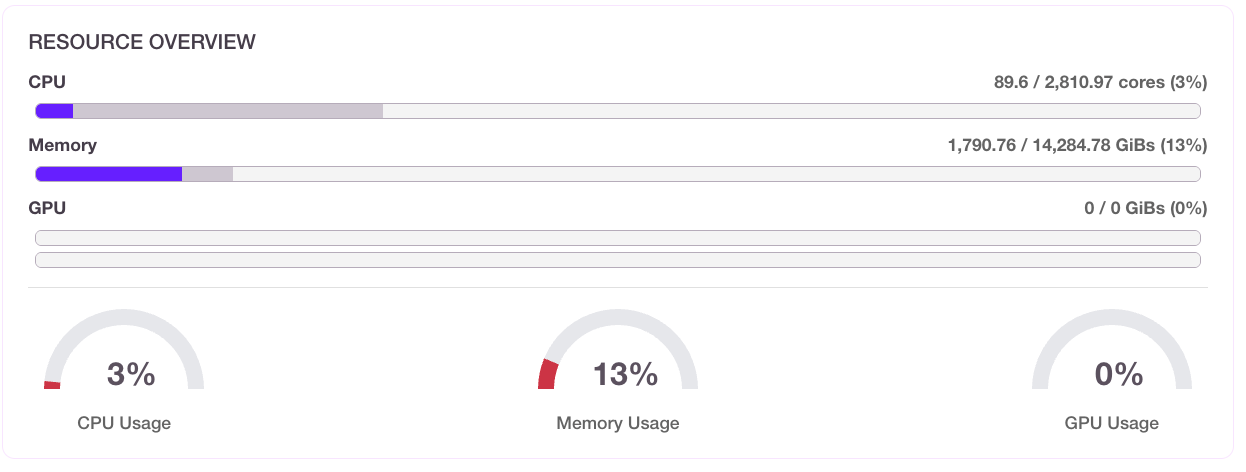

Cluster-wide utilization was only 12%.

Autoscalers added nodes because requests were too high, VPA recommendations lagged behind real demand, and scheduler decisions left large segments of nodes unused. Nothing was misconfigured. Kubernetes was doing exactly what it was built to do.

That was the moment we realized that Kubernetes does almost nothing to prevent waste on its own. Even healthy clusters drift toward inefficiency unless you constantly correct for it.

Once we saw this firsthand, we started noticing the same pattern everywhere. After a decade in infrastructure engineering, I’ve seen the same pattern repeated across teams: overprovisioned resources, underutilized nodes, oversized instances, and slow downscaling. All this has been driving the costs up; in fact, the CNCF report found that almost half of the users saw spending increase after adopting Kubernetes. Still, no other platform has matched it in terms of providing a unified framework for networking, storage, and process configuration at scale.

In this article, we will look at the origin of Kubernetes. We will also find out why early development priorities led to today’s problems and how we can potentially fix them.

Table of Contents:

- How did Kubernetes Come to Be?

- Compute and Memory: Overprovisioning in Kubernetes

- Role of Autoscalers and Where They Fail

- Bin Packing: A Strategy for Densely Packing Pods onto Fewer Nodes

- Efficient Bin Packing in Kubernetes

- Why Kubernetes Can’t Fix This

- Alternatives to Intelligent Workload Rightsizing and Smart Bin Packing

- Conclusion

How Did Kubernetes Come to Be?

Kubernetes was inspired by Borg, Google’s internal cluster management system that powered billions of container workloads with near-perfect efficiency. Borg was in charge of scheduling, scaling, and utilization through tightly controlled, predictive algorithms.

Parts of it were open-sourced and rebranded as Kubernetes, but the new system left much of Borg’s optimization logic behind. What we got is a flexible, API-driven system that’s great for developers yet blind to efficiency.

Kubernetes in this form is prone to overprovisioning, slow to react, and costly to run at scale; plus, its default settings make it occasionally inefficient. Unfortunately, the increased adoption of Kubernetes has also made these problems more ubiquitous.

Let’s look at the numbers.

Compute and Memory: Overprovisioning in Kubernetes

Workloads are dynamic by nature yet resources in Kubernetes are allocated statically, forcing developers to plan for peak times. Since scaling is often limited, teams tend to allocate more resources than necessary (also referred to as “overprovisioning”).

For example, JVM services often over-allocate resources because container‑unaware defaults and off‑heap memory aren’t accounted for. Fixed heap settings like Xms/Xmx are set too high, while metaspace and direct buffers push Resident Set Size far beyond the heap, causing inflated requests and frequent Out of Memory (OOM) errors when limits misalign. Oversized thread pools further mask true needs, prompting teams to reserve more CPU and memory than workloads actually use.

By enabling UseContainerSupport, tuning MaxRAMPercentage, lowering Xms, and sizing with real RSS (including off‑heap), teams can right‑size without compromising reliability.

LLM models such as DeepSeek are another example. They require a lot of memory when loading the model, often across multiple GPUs. After loading, DeepSeek requires little memory; however, those GPUs remain reserved.

This article analyzes resource wastage across different Kubernetes workload resource types. Jobs, CronJobs, and StatefulSets are overprovisioned more than half the time, and Deployments and DaemonSets waste slightly less than half. This is a fundamental flaw in Kubernetes, which cannot be solved by policy and configuration tweaks. The resources need to be managed better to optimize cost.

The root cause lies in the fact that the system itself wasn’t meant to optimize usage but to ease provisioning, as we’ve mentioned earlier. Kubernetes lacks predictability in resource placement, which should ideally be built into the cluster itself.

A benchmark for 2025 (2,100+ prod clusters) shows 10% average CPU utilization and 23% memory usage. This is a clear indicator of heavy underutilization.

Role of Autoscalers and Where They Fail

At times like this, we can use autoscalers, Kubernetes’ native tools designed to improve resource utilization. Vertical Pod Autoscalers adjust the resource requests/limits of existing pods, while Horizontal Pod Autoscalers adjust the number of pod replicas. The scheduler decides where those replicas run.Still, due to their design, they are prone to failures and feedback loops.

Vertical Pod Autoscaler Failures with Rightsizing

The VPA consists of a Recommender, which analyzes recent CPU and memory usage and proposes new request values, and an Admission Webhook Controller, which applies those recommendations by mutating the pod spec during admission and evicting and restarting the pod so the new sizes take effect.

When running the VPA in Auto or Recreate mode, the following issues may occur:

- The VPA resizes by evicting pods and requires pod restarts to apply recommendations. This triggers cascade failures. Some of the examples include:

- SQL Pods with 8 GB buffer pools take several minutes to warm up after a restart, causing query timeouts.

- Redis loses all cached data, forcing database hits.

- Java applications suffer JVM cold starts with garbage collection spikes.

- In microservices architectures, cascading restarts create 5–10 minutes of degraded performance across the entire system.

- The VPA observes an 8-day trailing window, basing recommended resources on last week's patterns. As such, it does not respond to seasonal changes well. During times of sudden spikes, the performance may actually degrade rather than improve.

Horizontal Pod Autoscaler Failures with Overprovisioning

How does the HPA help with scaling out? It increases or decreases the number of pod replicas based on demand, which makes it a strong fit for stateless, horizontally scalable applications.

However, when the HPA is configured to react to the wrong metrics, the HPA can cause more harm than good. CPU and memory aren’t good trigger options here, especially since the VPA might already be using them to understand whether it needs to adjust the size of the pod. In such circumstances, there can be a conflict between the HPA and the VPA, but more on that later.

It is best to configure the HPA based on business metrics, such as workqueue depth, latency, and requests per second. Still, these are not readily available, and they don’t translate directly into CPU and memory footprints. To make them easily available to the HPA to consume, you will need more sophisticated metrics setup within your Kubernetes cluster.

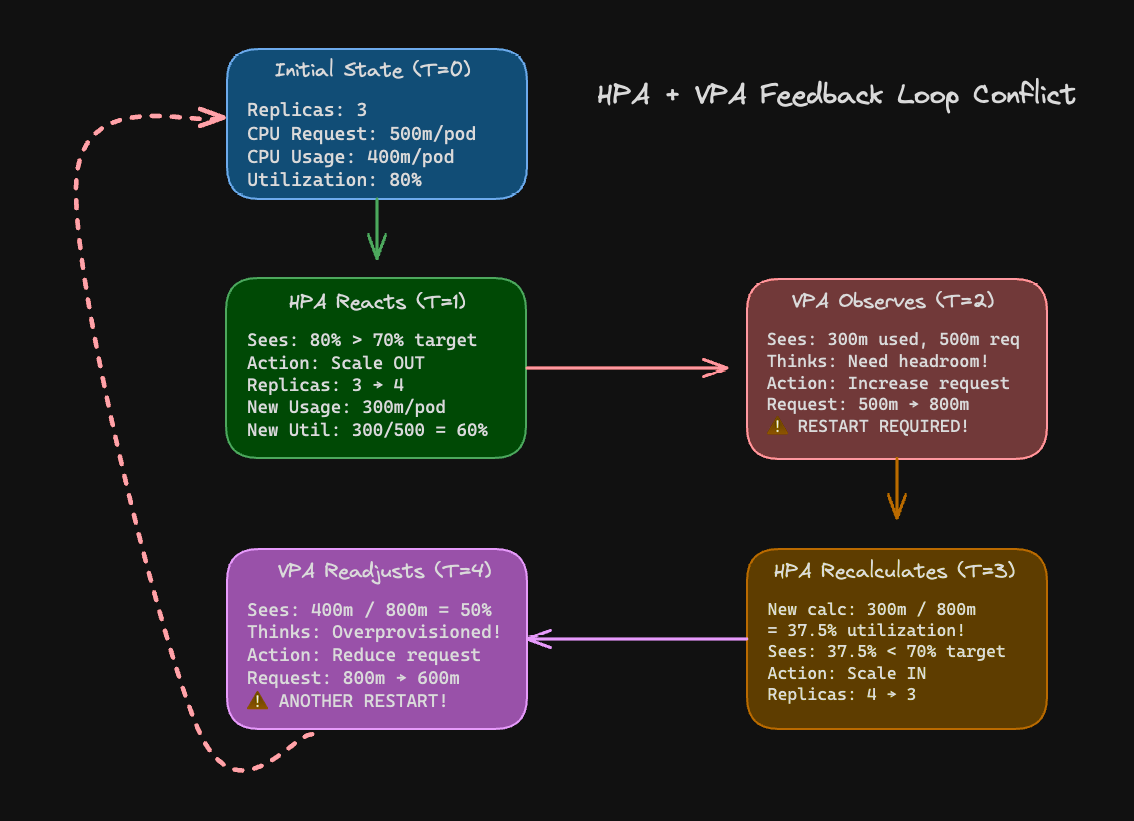

If you decide to use CPU and memory as triggers for the HPA, and you already have the VPA configured, the two autoscalers can conflict, potentially creating a feedback loop. Let’s take a closer look at how this happens.

How the HPA Can Cause Feedback Loop Conflicts with the VPA

The HPA causes conflicts with the VPA when both target the same metrics (namely, CPU/memory), creating feedback loops that oscillate between scaling out and scaling up. Here’s an example of how this happens:

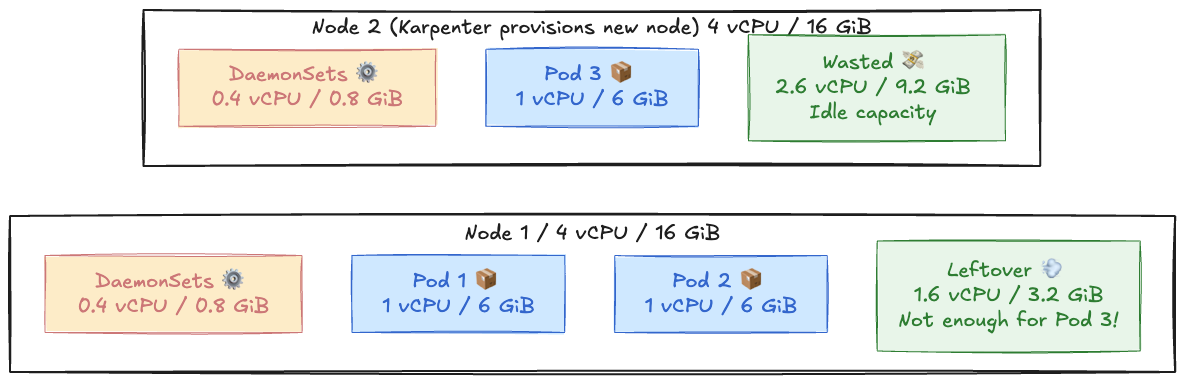

Figure 3 illustrates the HPA + VPA feedback loop where pods end up restarting over and over again as the HPA is trying to ensure that there are enough replicas and the VPA is optimizing for headroom.

The configurations for the HPA, VPA, and related deployment can be found here. The HPA calculates utilization as (actual CPU usage / CPU request) × 100. When the VPA changes the request (that is, increases or reduces the amount of CPU requested by the pod), the same usage produces a different utilization percentage, causing the HPA to go back on its scaling decision.

Now that we’ve covered rightsizing and overprovisioning, we can see the core issue is a bin packing problem. Next, we’ll explore what bin packing means in Kubernetes and how to address it so that the platform uses resources more efficiently.

Bin Packing: A Strategy for Densely Packing Pods onto Fewer Nodes

Bin packing in Kubernetes is a multi-dimensional resource allocation problem: when the issues related to memory optimization are solved, the CPU can remain underutilized, and vice versa.

The Kubernetes scheduler is responsible for provisioning efficiently, not just ensuring resilience. Kubernetes schedules pods, according to their requested CPU and memory.

Default Kubernetes Scheduler Policy and Its Downsides

The scheduler's default LeastAllocated strategy spreads pods across all available nodes to "balance load." For example, this can result in more nodes running at 20% utilization rather than fewer nodes at 70%.

The scheduler doesn’t see the actual usage, only the resource requests. It can't predict future requirements or understand workload compatibility. As a result, CPU-intensive batch jobs can land beside memory intensive databases, creating unusable resource fragments.

To improve the scheduling efficiency, we can use several policy tools available in Kubernetes:

- Cluster Autoscaler: CA automatically adds or removes nodes based on the shape of your pending pods. The problem here is that it would react only to unschedulable pods, not optimization opportunities, and work within predefined node groups rather than the whole instance catalog available to it.

- Anti-affinity rules: To ensure that pod replicas land on the correct nodes, we can set anti-affinity rules. This allows us to make sure that certain pods are not scheduled on specific nodes; however, when one of those nodes has enough resources, we might end up overprovisioning for the particular pod. These rules can be defined by the user in Deployments.

- Topology spread constraints: These constraints usually prefer geographic (nodal and zonal) distribution, ensuring that resources are packed properly on nodes that have capacity.

- Pod Disruption Budgets: PDBs can prevent consolidation by gating eviction when

minAvailableis set. While this is useful in quorum-style systems, it is unnecessary for the majority of stateless applications, as it’s not possible to drain the node when it’s set.

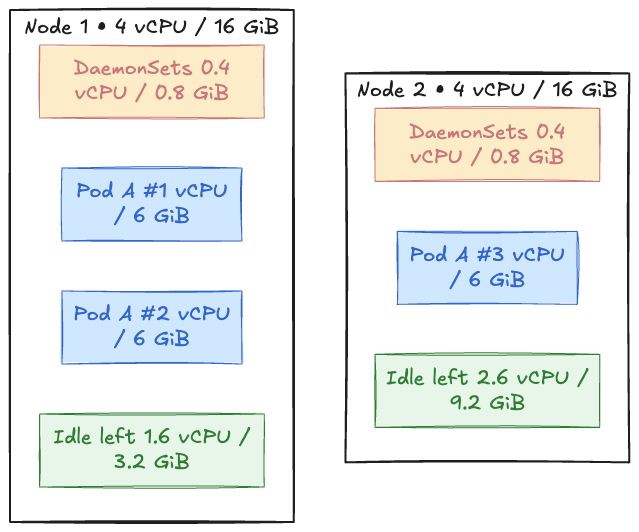

Let's look at an example node to see how the scheduler bin packing math can fail:

Given:

Per Node resource config: 4 vCPU / 16 GiB

Workloads we are going to create:

DaemonSets need 0.4 vCPU / 0.8 GiB, leading to a usable 3.6 vCPU / 15.2 GiB on the node.

Pod "A" (web) is the one we will be deploying on these nodes, so it needs 1 vCPU / 6 GiB (requests).

How will the workloads be created on the node:

Two "A" pods fit, considering that node resources of 2 vCPU / 12 GiB have been used, and we have leftover 1.6 vCPU / 3.2 GiB. A third "A" pod needs 1 vCPU / 6 GiB, but since we are running low on memory, it's going into the Pending state.

The Autoscaler adds a new node even though 45% CPU on the first node still sits idle. At scale, this problem can lead to a lot of wasted resources, as pods of different shapes can make the bin packing problem even more complex.

Efficient Bin Packing in Kubernetes

Several tools can help us solve the bin packing problem, including the Cluster Autoscaler, which we have discussed above, and Karpenter, which is designed to be built with cloud providers and improve the limitations of CA.

Cluster Autoscaler

The Cluster Autoscaler watches for pending pods and resizes node groups through the cloud provider. It operates at the node-pool level and assumes you’ve predeclared instance families, sizes, min/max counts, and similar. These node pools need to be created ahead of time. If the correct shaped node pools are not defined beforehand, several problems can occur:

- Predefined node pools: If the right shape for the pod is unavailable, the scheduler assigns the pod to the nearest fit rather than the best fit, leaving big, uneven gaps on nodes. This extra headroom adds to the cost of the cluster.

- Coarse bin packing: Since a pod shape is not considered when assigned to a node, CA brings up whole nodes in a few fixed sizes. As a result, mixed workloads may not fit well, leaving CPU or memory that cannot be used.

- Slow scale-down and stranded capacity: Partial nodes can block better packing because the Autoscaler won’t drain and consolidate them quickly enough. When a pool’s AZ or instance family is tight, the CA also keeps asking the same pool. Usable capacity in other families/AZs sits idle while pods wait, and packing suffers across the board, which leads to underutilization with some nodes that are not able to scale down and the pods that are not allocated in the necessary AZs.

The Cluster Autoscaler is a native tool in Kubernetes but we need better node lifecycle management to ensure the correctly shaped and sized nodes are allocated.

Karpenter

Karpenter responds to pending pods by consolidating, draining, or replacing nodes while respecting Pod Disruption Budgets. However, it's purely reactive.

The bin packing algorithm is simple: it matches pod requests to available instance capacity. A node is only removed after all its pods are drained. Since Karpenter doesn't predict future needs, its scaling decisions can be inefficient.

This creates two problems:

- Lack of proactive optimization: Karpenter won't move pods around to improve placement. It simply waits until a node is empty, then deletes it.

- Fragmented resources: Decisions rely on pod requests, not actual usage. This causes resource fragmentation if pods request more than they actually use.

Limited Instance Diversification for Deployment

The extremely specific node requirements, such as a single instance type, limited availability zones, or strict resource ratios like CPU to memory, can make it hard for Karpenter to find optimal instances. This forces the scheduler to pick mismatched nodes at the wrong time, leaving gaps that new pods can’t use.

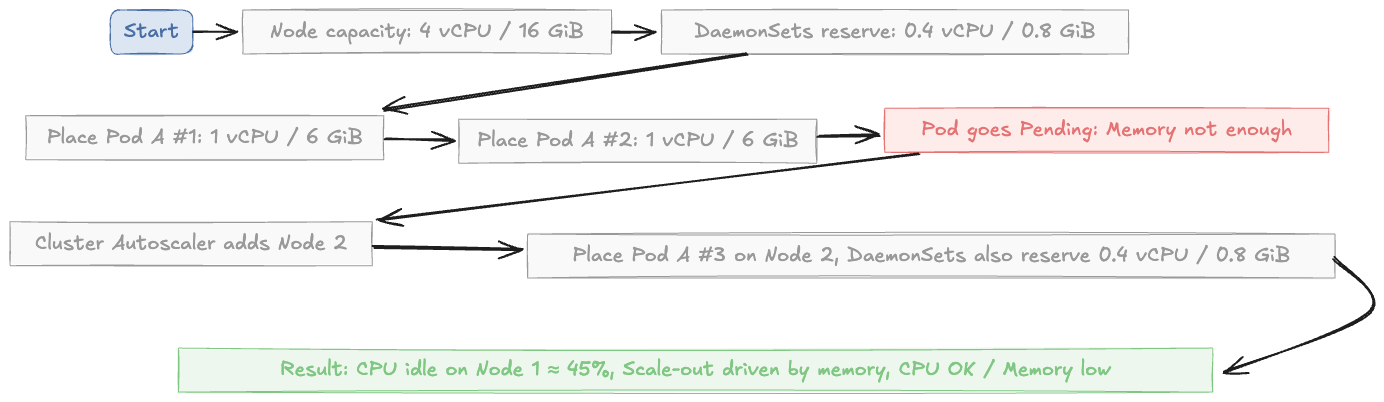

DaemonSets and Topology Edge Cases

Required DaemonSets, zone/hostname spreads, and anti-affinity rules reserve fixed CPU and memory on every node. This overhead doesn’t always align with the shape of your application pods, so capacity gets fragmented.

Here’s an example:

- Each node = 4 vCPU / 16 GiB

- DaemonSets take 0.4 vCPU / 0.8 GiB, leaving 3.6 vCPU / 15.2 GiB usable

- Your pods = 1 vCPU / 6 GiB

You can fit two pods (2 vCPU / 12 GiB). The third one fits CPU-wise but fails on memory (needs 6 GiB, only 3.2 GiB free).

Karpenter sees no space and spins up a new node, even when an existing one is mostly idle, and that’s how you waste resources.

While it does solve some of the Cluster Autoscaler issues and helps with rightsizing and workload optimization, we can see that it does not provision and move resources proactively when necessary. If it could combine workload rightsizing and bin packing, it would be far more powerful.

Let’s see how these can be combined into a more sophisticated system that focuses on continuous optimization for cost and resource utilization.

Why Kubernetes Can’t Fix This

There is a natural question that comes up once you see how much waste Kubernetes creates. Why not simply improve the scheduler or autoscalers and fix the problem inside the platform?

The short answer is that Kubernetes was never designed to act as a global optimizer. Several architectural constraints make efficiency very hard to solve inside core Kubernetes.

- Kubernetes is built for reliability and portability, not efficiency. The system inherited some ideas from Borg, but not the predictive algorithms that made Borg efficient. Kubernetes favors modular APIs and vendor neutrality, which limits deeper optimization logic.

- The scheduler only sees requests, not real usage. It has no visibility into historical patterns, real-time utilization, warm-up behavior, or workload interactions. This makes optimal placement almost impossible.

- Pods are not designed to move once scheduled. Without native migration or checkpoint and restore, Kubernetes cannot rearrange workloads, consolidate nodes, or fix poor placements. Once a pod lands on a node, it stays there until it restarts.

- Autoscalers work independently. HPA, VPA, the Cluster Autoscaler, and Karpenter each solve a small part of the problem. They do not coordinate and often make conflicting choices.

- Core changes move slowly. Any shift in scheduling or autoscaler behavior requires long discussions, strict backward compatibility, and agreement across many vendors. Innovation tends to happen outside core Kubernetes.

Because of these constraints, Kubernetes rarely converges toward efficient usage on its own. The platform can scale your workloads, but it cannot easily optimize them.

Alternatives to Intelligent Workload Rightsizing and Smart Bin Packing

Kubernetes makes it easy to overprovision and increase infrastructure costs by default. The scheduler spreads pods to increase resilience, the Autoscaler adds or removes nodes, and the Vertical Pod Autoscaler forces restarts to adjust requests.

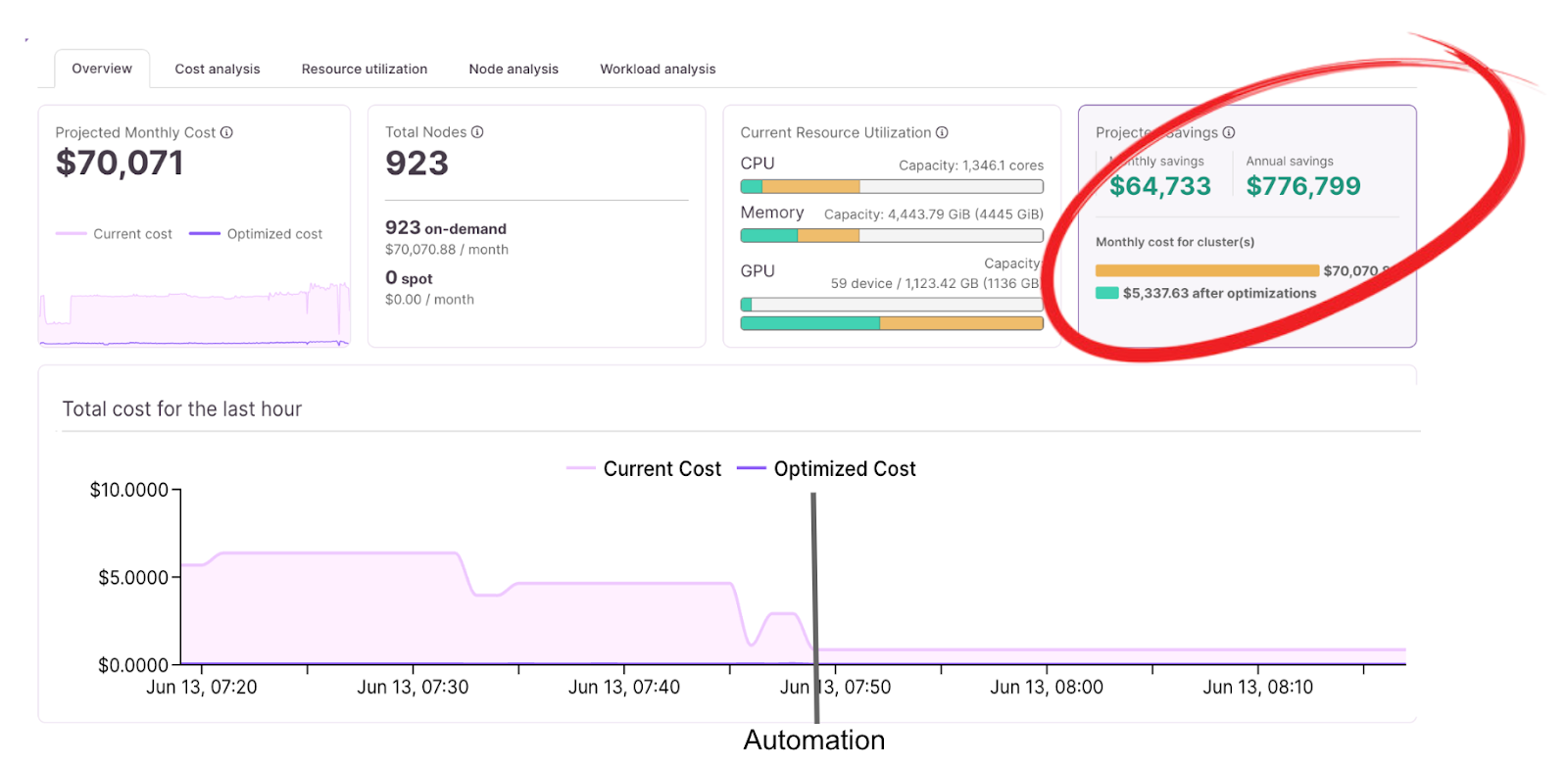

In order to reduce spending, we need tools that can visualize cost and connect it to the type of workloads running on the cluster. Let's see how we can address these gaps:

- Continuous bin packing and live consolidation: To optimize bin packing, teams need to observe real-time pod usage and apply workload-specific policies for different workloads. For example, we can consolidate background jobs easily, but we need to allocate more resources to latency-sensitive APIs. A more effective approach would combine continuous rightsizing, proactive bin-packing, and live workload migration. This requires capabilities Kubernetes does not yet provide — such as CRIU-driven checkpoint/restore, fine-grained pod-level telemetry, and intelligent consolidation algorithms.

- Automated rightsizing: You can also use tools like DevZero to help rewrite resource allocations based on live and historical usage. They ensure services are properly sized over time and eliminate waste generated by the “set once, forget forever” approach.

- Proactive scaling: It’s important to combine recent trends with historical load to warm up capacity before spikes in traffic. This way, you can avoid HPA cold starts or cascade restarts during demand surges. Platforms that enable you to get a deeper look into these metrics really help drive home the effects of predictive scaling to save cost.

There’s a growing ecosystem of tools and research exploring smarter scheduling, predictive autoscaling, and even live pod migration. These ideas are promising but early.

Conclusion

Kubernetes solved deployment standardization, not efficiency. Fixing the latter requires combining predictive autoscaling, workload-aware scheduling, and real utilization monitoring — concepts that were core to Borg but never fully implemented in Kubernetes. Until these capabilities become native, teams will continue stitching together partial solutions or building their own.